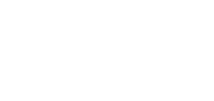

Nadia Sanchez works to improve the lives of women and girls in distressed areas of Colombia and nearby.

peace agreement reduced the open warfare, deadly flare-ups still occur and the effects of the past are still deeply felt.

Beyond Colombia, Nadia and the She Is Foundation also work with women and girls in nearby countries, who may face other forms of disruption or deprivation. For all concerned, the Foundation develops what it calls “a sustainable women’s empowerment model.” Along with providing basic humanitarian aid, the Foundation conducts education-and-support programs that range from business and social entrepreneurship to peacemaking and tech innovation for girls. (For example, She Is connects them virtually with the NASA Space Center in Houston, and recently sent 31 Colombian girls there for an in-person immersion experience.)

Altogether, the work that Nadia leads has touched over 15,000 women and girls thus far. Here are highlights from her interview with World Woman Hour.

Q: Nadia, what put you on the course to do what you’re doing now?

Nadia Sanchez: This is something that I had been dreaming about for years. I grew up in a family of teachers, where I always saw my mother helping women and girls. Later, I worked for the Inter-American Development Bank in Washington, so I created the She Is project initially for the Bank. When the Bank rejected it, I decided to return to Colombia, to discover that reality and to work and walk through so many places, so many hostile terrains. I wanted to know the truths and stories of women and girls who were looking for great opportunities. And that’s when I founded She Is as a nonprofit organization.

What I thought at first was a frustration, a rejected idea, has turned out to be a foundation with great impact for women and girls in Latin America. Its purpose is to create a global agenda that will improve the quality of life for many women and girls who have been invisible—both in the countryside and everywhere.

Q: What inspired your passion for women’s issues?

Nadia: There is still a historical debt that society owes to women and girls, in regard to visualizing a better future and being able to believe and create. I think that is what motivates me the most. And I can transfer that passion to others, so that more people have the opportunity to become great women who not only conquer high positions, but also achieve their hopes and dreams.

Today women are passionate, and I love it. I am passionate about working for them, because it has allowed me to lead, and to carry the voices of all those women who have been silenced.

Q: The work that you do is very challenging. What have you learned about failure, and overcoming failures?

Nadia: What I have learned is to embrace failure and generate a thousand solutions. I always say that failure is a new opportunity, a new window that opens in the middle of 99 doors that have been closed.

When you embrace failure, you have to understand that it is part of the essence of a process: not only a part of the essence of trying, but of the path of life. Many times when we say “I failed,” we think that it is synonymous with defeat. But when we talk about failure, we should mean that we have done so many tests along the way that today, we know the best way to do it—because we embraced failure and faced our fears.

That fear is not a constant. On the contrary, it is the little kick that can drive us. And once I learned to embrace failure, I was no longer afraid of it.

Q: It’s so important, isn’t it, for girls to understand that failures are part of the evolution of an idea?

Nadia: That’s right. Sometimes they question us and tell us “I can’t fail!” It’s hard for them to understand that in the end, it’s part of the process.

Q: If you could talk to a much younger version of yourself, what advice would you give?

Nadia: I always question myself, and I even love writing about that inner child that we all carry. I would say to my inner child not to question myself so much. When I was a child, I had to feel that everything was perfect and in order. I would have loved to understand that life is simply a process of imperfections.

So the best advice is, let’s not judge ourselves so much. Let’s not demand so much of ourselves that it keeps us from living our dreams. As we say here in Colombia, don’t take it so hard every day that you don’t let the weathervane of your life flow. I always tell this to the girls I work with: Keep believing in yourself without judging yourself so much, like a perfectionist. Because the wonder of life is in the imperfections.

Q: What changes can be made, so that more women can be more effective leaders?

Nadia: A big part of those changes is to understand that effective leadership starts from human leadership. We women are by nature maternal, and that must be reflected in empathy for others. We have to put ourselves in someone else’s shoes, three sizes smaller, to understand the ability to lead. An effective leader does not destroy voices; an effective leader guides voices.

And so, women today in global movements are preparing to lead—but they will lead with transformation, and with humanism. They will lead us toward a sensibility of empathy, of human fellowship, and of guidance.

Q: To what extent is women’s health care important for the future?

Nadia: It is extremely important. It is essential to talk about women’s health care as a necessity, not a privilege that is available only to some. All women and adolescent girls in the world deserve the right to decent menstrual health, to mental health. To be able to give birth with the comforts and conditions that some women have, but not all.

In the future, we must talk about humanizing and raising awareness of women’s health. We cannot avoid issues like teenage pregnancies, or clandestine abortions, or topics such as breast cancer and uterine cancer. These things affect women and girls throughout their entire life processes of growth, gestation, and maturity. We must understand that health concerns for women and girls are different than they are for men. And for women in many regions of the world, access to knowledge and care continues to be a privilege. We have to achieve health care that is truly universal.

Q: Are there particular health issues for women that you would want to call attention to?

Nadia: At She Is, we have an integrated model for empowering women, to give them the entrepreneurial and innovation tools to get ahead. And one thing we have to work on with them is mental health. In places where there has been armed conflict in Colombia, we have had to work with women literally from scratch, rescuing the survivors. They may have panic attacks or other mental health issues. Also, part of the problem is the amount of overload in women’s lives. The responsibility for family care falls much more on women, and this combines with being in a conflict environment to put pressure on their mental health.

So, while there are endless factors that we are passionate about working on at the foundation, health is part of the base of the pyramid. Along with checking that the women’s physical health needs are being met, which could be anything from having sanitary napkins to an early diagnosis of an illness, we work with them throughout that mental and emotional transition, from resilience to reconciliation. They need to recognize themselves to believe what kind of people they are, and how far they are going to go and what they are going to achieve.

Q: Do you have a superpower?

Nadia: I believe that all of us have a superpower. Part of my superpower is to give my best talents and compassion to help more women develop and believe in what they are capable of doing. I always say that every woman’s greatest superpower is being able to look back and see how many women you’ve helped to shine.

Q: People who have been an inspiration to you?

Nadia: Ever since I was a child, my father has motivated and inspired me. As children we know that our mother is an important figure, and obviously I am not leaving my mother aside. But I love to name my father because, among masculine figures, he has been an empowering dad. In addition to how he has talked to me and guided me, he has had an impressive life story. Seeing how he embraced failure in impossible moments—waking up every day to give a smile in the midst of chaos—has helped to give me the same resilience and strength. And it has helped me to transmit those qualities to other women.

Also I would mention many great women leaders who can be inspirations to all of us. One is Nadia Murad, the young Iraqi woman who survived captivity and torture in her country, during the conflicts there, and who became a human rights activist and Nobel Peace Prize winner. One who inspires me here in Colombia is Juana Ruiz, a National Peace Prize winner, who brought thousands of women forward after the armed conflict. And while of course we admire famous celebrities, I think of the thousands of women in Colombia who have worked with our foundation. We should also admire these “local celebrities” who transform us and generate change!

Q: Do you have a message to young women or girls about what they can do today?

Nadia: We are changing the world. Today you can be part of this in a very simple way, which is to believe in your dreams and make other girls believe. Our voices will never be silenced. We will always fight for what we think we can be—whether it is an astronaut, a scientist, a teacher, or anything that it is possible to dream of being. So, always believe. Never shut down your voice. Fight for those dreams and ideals.